Introduction

This document presents 23 guiding principles for the preparation of impact analyses supporting proposed code changes. It is intended to be used by the Canadian Board for Harmonized Construction Codes (CBHCC) development committees when developing proposed changes for public review.

It is important to note that these are general guidelines; each proposed change will be different in nature and may require special considerations beyond the principles presented herein. The applicability of each principle should be determined by the CBHCC development committee(s) responsible for the proposed change being developed.

Definitions

Benefit

An impact that produces positive changes or advantages, good and helpful results or effects.

Cost

An impact that results in increased monetary expenditure, reduction in level of performance with respect to an objective of a code, or any adverse impact on the natural or built environment.

Impact

Consequences—intended and unintended, positive as well as negative, specific to an objective or in general—that may result from the implementation of a proposed change.

Impact analysis

- Methods and processes that are used when describing the positive and negative consequences resulting from the implementation of a code change.

- A systematic practice where assumptions, methods and results are presented in such a way that they can be tested by other analysts.

- A technique of evaluation to permit consideration of the full impact of a proposed change, including those impacts that are not quantifiable in monetary terms.

- The description of the positive and negative consequences developed to support a proposed change(s).

Qualitative assessment

An evaluation that is reached by compiling, comparing and evaluating input that is not numerical but that has been obtained through various indefinable means. This includes any descriptive information that explains the proposed change without requiring numerical comparison (for example, situations, experiences, behaviours, history, etc.). This method assesses an impact, but cannot measure it.

Quantitative assessment

A comparison of data that can be presented in a numerical form. This can be anything that can be counted, measured, and numerically compared to provide a numerical conclusion.

General issues

Prescriptive requirements versus performance-based requirements

The effort required to analyze the costs and benefits of a prescriptive requirement is different from the corresponding effort required for a performance requirement.

Prescriptive requirements state a specific compliance option, which means that building materials and construction techniques on which costing of the proposed change is based are known. On the other hand, performance requirements state a desired outcome and leave the construction compliance method up to the designer. For example, multiple construction methodologies could be used to achieve the stated performance measure, and each one would presumably entail different costs.

For the assessment of benefits, the change in the performance level of the building or its components that would result from implementation of the proposed change may first need to be established. The change in performance level will likely be more difficult to determine for prescriptive requirements, where the performance level of the existing requirement and/or of the proposed requirement may be unknown or difficult to assess. In the case of performance-based requirements, it is more likely that their performance levels will be explicitly stated or more easily determined.

The principles that follow take the differences between prescriptive and performance-based proposed changes into account.

Principles and analysis

General principles

Principle 1:

An impact analysis must be prepared for all proposed changes.

The term “all proposed changes” includes changes that present another option to an already established acceptable solution in Division B. This term also includes so-called “enabling provisions”, which are requirements that only come into effect if the code user chooses to incorporate the element that is the subject of the provisions. “All proposed changes” also includes changes that add a standard reference.

Principle 2:

The level of complexity of the impact analysis should be proportional to that of the proposed change.

It would not be reasonable or congruent with the feasibility of the process to require a rigorous analysis for all code changes as the vast majority of the analyses will be carried out by the CBHCC development committees.

Proposed changes that fall within the criteria of “minor tasks” would therefore warrant a very simple analysis.

Proposed changes that are contentious or that have significant policy or cost implications would warrant a complex analysis that may require the hiring of a specialized consultant.

On the spectrum between simple and complex, the level of complexity of the impact analysis should be proportional to the complexity of the proposed change.

Principle 3:

A quantitative analysis should be performed when possible; otherwise, a qualitative analysis is required.

Impact analyses can be expressed in quantitative terms, in qualitative terms, or as a combination of the two. A quantitative assessment should be performed where possible to support the justification and rationale of the proposed change. Where this is not possible, a qualitative analysis is required.

Principle 4:

An impact analysis that affects dwelling units must use the dwelling unit archetypes found in Appendix A[1] where relevant to a change.

The use of archetypes for dwelling units allows the comparison of multiple proposed code changes to a common benchmark. This provides an understanding of how the impact of one proposed change compares to that of another. Cumulative analysis can also be performed using this approach. The archetypes supplied for dwelling units are archetypes that address more affordable dwelling units.

Analyses using other archetypes are acceptable if performed in addition to those found in Appendix A. When conducting an impact analysis on dwelling units, use the dwelling unit archetypes from Appendix A if they are relevant to the change. If no relevant archetypes are used, provide a rationale, such as when a proposed change in provisions related to Part 3 buildings does not impact any of the Part 9 archetypes.

Principle 5:

The impact analysis should be restricted to the direct costs and benefits (indirect costs and benefits can be analyzed separately if deemed of interest).

The impact analysis should include the direct costs and benefits involved in the implementation of the proposed change.

Examples of direct costs are costs related to objectives of the codes referenced in the proposed change. These can be construction materials and equipment requirements, which can also include additional costs of land and transportation costs, and labour costs, which can include design, administrative and professional involvement fees.

Incrementally incurred costs may need to be considered by the committees in their analysis, for example site implications for a possible increase in a building footprint, or loss of useable space due to a proposed change.

Indirect costs are any costs that fall outside the scope of the Codes, for example training cost, the maintenance of buildings, or the purchase of standards. Indirect costs are often difficult if not impossible for the CBHCC development committees to assess.

Direct benefits are the benefits related to the applicable code’s objectives that the proposed change is intended to achieve:

- improved safety

- potential reduction in design, construction and development costs

- reduced negative health implications

- reduced energy costs

- flexibility in design

- avoiding discrimination of new technologies (levelling the playing field)

- clarification of provisions to assist in interpretation and enforcement

As with indirect costs, indirect benefits fall outside the scope of the Codes and are difficult, if not impossible, for the CBHCC development committees to assess: e.g., reduced insurance costs, reduction in infrastructure costs.

Indirect costs and/or benefits are worth noting on the proposed change. However, it is a concern that requiring their quantitative assessment would expand the analysis beyond the scope of the Codes and place an undue burden on the CBHCC development committees such that the complexity of the analysis would exceed the capacity of the system to complete it.

Principles related to benefits

Principle 6:

A benefit is generally defined as an increase in performance level or a reduction in construction cost, or a combination thereof.

In the majority of cases, a benefit will entail a reduction in monetary costs or an increase in performance level, which may, in turn, bring about monetary savings. Typical examples of benefits include:

- removing a hazard or reducing the risk associated with the hazard

- improving the performance of buildings

- clarifying code provisions that ease enforcement and save time, or

- offering design flexibility or less costly acceptable solutions to the industry

It should be noted that what is perceived as a benefit by one development committee may be viewed as a cost by another.

Principle 7:

Where benefits of proposed changes are related to an increase in performance level, the net benefit must consider the probability of occurrence.

Where the net benefit results from an increase in performance level and where a formula can be used to estimate it, the net benefit is the product of the value of the benefit times the probability of occurrence.

Principle 8:

When there is uncertainty about the quantitative analysis of benefits (the probability of occurrence and/or the dollar value of the benefit), a likely range of values should be provided.

In many cases, it may be difficult to acquire definitive numbers for the probability of occurrence and to assess the monetary value of a benefit. Where these parameters cannot be determined with a reasonable degree of certainty for the specific case covered by the proposed change, the benefit should be expressed in terms of a likely range of values.

Principle 9:

The direct benefit should relate directly to one or more approved code objectives that the proposed change addresses.

To keep within the scope of the Codes, the direct benefit should relate specifically to at least one of the Codes’ objectives: energy use and water use efficiency, fire and structural protection of buildings, fire and structural safety, health and accessibility. Each objective may have its own unique characteristics. Where a single provision is attributed to multiple objectives, only one impact analysis is required. Where objective-specific principles apply (Principles 10-14), they should be considered in the context of all other objectives to which a provision is attributed.

Principle 10:

The benefits of proposed changes linked to the objective of energy use and water use efficiency linked to under Environment should be expressed in quantitative terms as monetary savings or as incremental annual energy or water savings.

Energy use and water use efficiency under Environment – The benefits of proposed changes linked to these objectives are typically quantifiable in terms of monetary savings. While there is typically no statistical analysis related to probability of occurrence associated with such provisions (as is often the case for health and safety-related objectives), assumptions or benchmarks can be established that facilitate predictions on national annual energy or water use savings. If deemed relevant, the committees can note large-scale benefits, such as positive effects of a proposed change on community infrastructure, in qualitative terms.

Principle 11:

The benefits of proposed changes linked to the objective of fire and structural protection of buildings should be expressed in quantitative terms as monetary savings resulting from the value of the benefit or as an incremental benefit calculated as the product of the benefit times its probability of occurrence.

Fire and structural protection of buildings – The benefits of proposed changes linked to these objectives are also quantifiable in terms of monetary savings, however, there is a statistical component related to probability of occurrence that needs to be factored in the equation. The CBHCC committees should strive to determine this probability of occurrence to yield a net benefit in dollars.

Principle 12:

For proposed changes linked to the objective of safety, the aspect of the benefit related to injury should be expressed in quantitative terms as monetary savings resulting from the value of the benefit times the probability of occurrence of the hazard, and the aspect related to loss of life should be expressed in terms of number of deaths avoided.

Safety – The safety objective relates to the risk of injury and/or death resulting from a sudden hazardous event, such as an accident, fire, or failure of a building system. Benefits related to injury reduction should be based on medical treatment costs averted over the life of the injured person times the probability of occurrence of the hazard. The aversion of loss of economic productivity and reduction of negative impact on quality of life are examples of indirect benefits related to the safety objective.

Principle 13:

For proposed changes linked to the objective of health, the aspect of the benefit related to illness should be expressed in quantitative terms as monetary savings resulting from the value of the benefit times the probability of occurrence of the hazard, and the aspect related to illness should be expressed in terms of illness avoided.

Health – The health objective relates to the risk of illness that may or may not lead to death. Direct benefits related to illness reduction should be based on comprehensive medical, caregiver and transportation costs averted over the life of the ill person times the probability of occurrence of the event that caused the illness. Similar to the safety objective, the aspect related to loss of life (in this case, death resulting from illness) should be expressed in terms of number of deaths avoided. The aversion of loss of economic productivity and reduction of negative impact on the quality of life are examples of indirect benefits related to the health objective.

Principle 14:

For proposed changes linked to the objective of accessibility, the benefits should be expressed in quantitative terms to the best possible extent; else, a qualitative assessment is required.

Accessibility – The accessibility objective relates to the reduction of impediments to the access of buildings and their facilities/amenities. Benefits related to this objective are largely societal in nature and will typically be expressed in qualitative terms. In some cases, it may be possible to describe the benefits in terms of numbers of persons assisted and/or building types impacted.

Principles related to costs

Principle 15:

A cost is generally defined as reduction in performance level or an increase in monetary cost.

The corollary to the benefit being a positive impact of the proposed change is that a cost is perceived to be negative. In the majority of cases, cost refers to an increase in monetary costs introduced by the proposed change. It is also possible to express a reduction in performance level as a cost, for example if the implementation of a proposed exemption brings about an increase in hazard in some situations.

Principle 16:

Monetary costs refer to the incremental capital cost of construction, but, depending on the scope of the proposed change, might include operational costs.

The monetary costs should be based on the incremental capital cost of materials and labour; in other words, on the difference between the cost of Code-compliant construction to the current code and the cost of construction as described in the proposed change.

With the exception of the National Fire Code of Canada (NFC), operational issues are not within the scope of the Codes; however, reduced operational cost savings are used to rationalize proposed changes in the National Energy Code of Canada for Buildings (NECB) even though the NECB does not apply to the operation of buildings.

The cost analysis should be transparent and support evaluation and decision-making about code change proposals for different regional areas in Canada. The seven regions to be evaluated are:

- Alberta

- Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island)

- British Columbia

- Manitoba and Saskatchewan

- Northern Canada (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon)

- Ontario

- Quebec

The cost analysis should be transparent and developed and reported in a manner that supports evaluation and decision-making about code change proposals by authorities having jurisdiction. Cost analysis should be reported in a manner that supports the impact assessment requirements of authorities having jurisdiction such as building archetypes, stakeholder impacts, and cumulative impacts of related code change proposals.

In some cases, a proposed change may address an issue whose costing may require consideration of demographic and geographic differences, such as urban, rural, and remote locations. An example of such an exception is a proposed change related to residential sprinklers: their installation in areas connected to a municipal water system would entail substantially different costs than in areas served by wells. The CBHCC development committees must be cognizant of underlying factors that could affect the cost analysis.

Principle 18:

Costing tools, such as RSMeans, should be used to determine the incremental capital cost of construction.

Costs should be based on a standardized and readily accessible source of information. Many of the CBHCC committees have successfully used the RSMeans cost manuals to perform their analyses. These manuals contain factors that take into account construction costs by geographic location, which facilitate the determination of a national cost by weighting according to population.

Principle 19:

A quantitative cost analysis is the default approach for prescriptive proposed changes; in rare cases where it is not possible to do so, a qualitative cost analysis is required.

As prescriptive provisions typically present an exact construction methodology, a quantitative cost analysis of such proposed provisions should be viable.

Principle 20:

A qualitative cost analysis is acceptable for performance-based proposed changes when the change does not apply to dwelling units and the cost of implementation is estimated to be no more than 0.5% of the total cost of construction for the building.

Performance-based proposed changes can be implemented through a variety of design and construction methods; hence, the effort to assess the costs of such proposed changes can be exponentially greater than that required for prescriptive changes. As such, performance-based proposed changes have a minimum threshold below which a qualitative analysis is sufficient, which is set at proposed changes that amount to no more than 0.5% of the total construction cost for the building. For these proposed changes, a qualitative cost analysis rather than a quantitative one is deemed acceptable.

Principle 21:

A quantitative cost analysis is required for performance-based proposed changes impacting any dwelling unit archetype.

Performance-based proposed changes can be implemented through a variety of design and construction methods. However, there is a need to assess the costs of such proposed changes on dwelling units. For these proposed changes, a quantitative cost analysis is required for the archetypes. If an impact analysis is required for other building types, a qualitative cost analysis is acceptable if the cost of implementation is estimated to be no more than 0.5% of the total cost of construction for the building.

Principle 22:

A quantitative cost analysis is required for performance-based proposed changes, if the cost of implementation is projected to be more than 0.5% of the total construction cost of the building. This analysis should be based on a representative number and type of archetype buildings most likely to be impacted by the change. The results should then be weighted by percentage of buildings constructed.

Assessment of cost versus benefit

Principle 23:

The costs and benefits analyses should be transparent and clearly stated so that stakeholders can easily compare them with their particular purposes in mind.

Caution is advisable when comparing costs and benefits analyses that are based on projections of future scenarios. They are inherent in such analyses as net present value, which uses discount rates, inflation rates and the assessment period.

Life-cycle costing is another widely used form of analysis; however, it is an optimization tool that accounts for issues that are beyond the scope of the Codes, such as maintenance costs, and therefore should not be used.

The cost-versus-benefit assessment should be easy and straightforward; e.g., where specific formulas or assumptions have to be used, these should be stated.

Tools

The following table presents a simple way to determine the degree of complexity of a proposed change.

Table 1: Determining the complexity of a proposed change

| Characteristics of a simple proposed change | Degree of complexity (low to high) | Characteristics of a complex proposed change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-controversial | Controversial | |||||

| No policy issues | Policy issues | |||||

| Within scope of Codes | Beyond scope of Codes | |||||

| No enforcement issues | Significant enforcement issues | |||||

| Very low or no costs | High costs | |||||

Text description of Table 1

The table organizes proposed changes into two categories: simple and complex, and compares them based on five key criteria.

The first criterion is whether the change is controversial. A simple proposed change is non-controversial. A complex proposed change is controversial.

The second criterion is whether the change relates to a policy issue. A simple proposed change is not related to a policy issue. A complex proposed change is related to a policy issue.

The third criterion is scope. A simple proposed change is within the scope of the National Model Codes. A complex proposed change is outside the scope of the Codes.

The fourth criterion is enforcement issues. A simple proposed change has no enforcement issues. A complex proposed change has significant enforcement issues.

The fifth criterion is costs. A simple proposed change has very low costs or no costs. A complex proposed change has high costs.

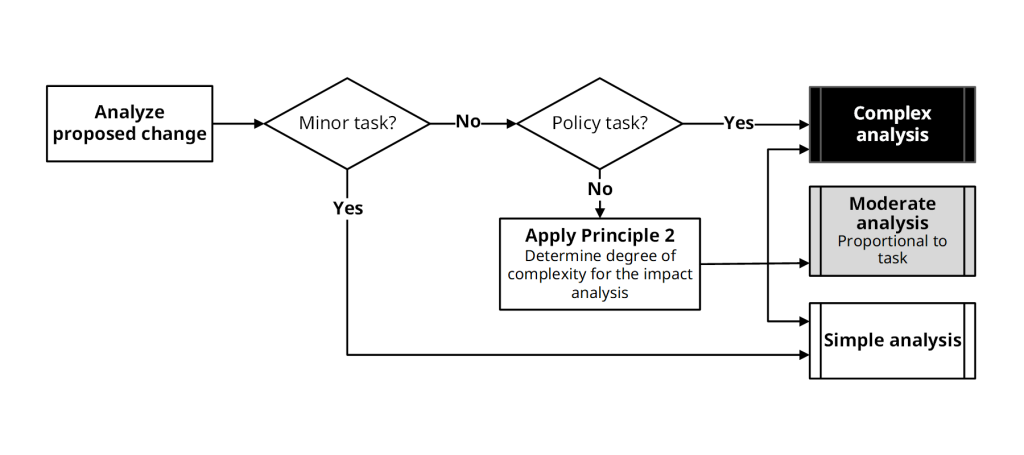

Once the complexity of the proposed change has been established, the proportional level of impact analysis should be determined using the flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Determining whether a simple, moderate, or complex impact analysis is required

Text description of Figure 1

The chart shows the decision steps for determining whether a simple, moderate, or complex impact analysis is required

Question 1: Is it a minor task?

- If your answer is Yes, a simple analysis is required

- If your answer is No, go to question 2

Question 2: Is it a policy task?

- If your answer is Yes, a complex analysis is required

- If your answer is No, apply Principle 2: Determine degree of complexity for the impact analysis. Depending on the outcome, a complex, moderate, or simple analysis will be required.

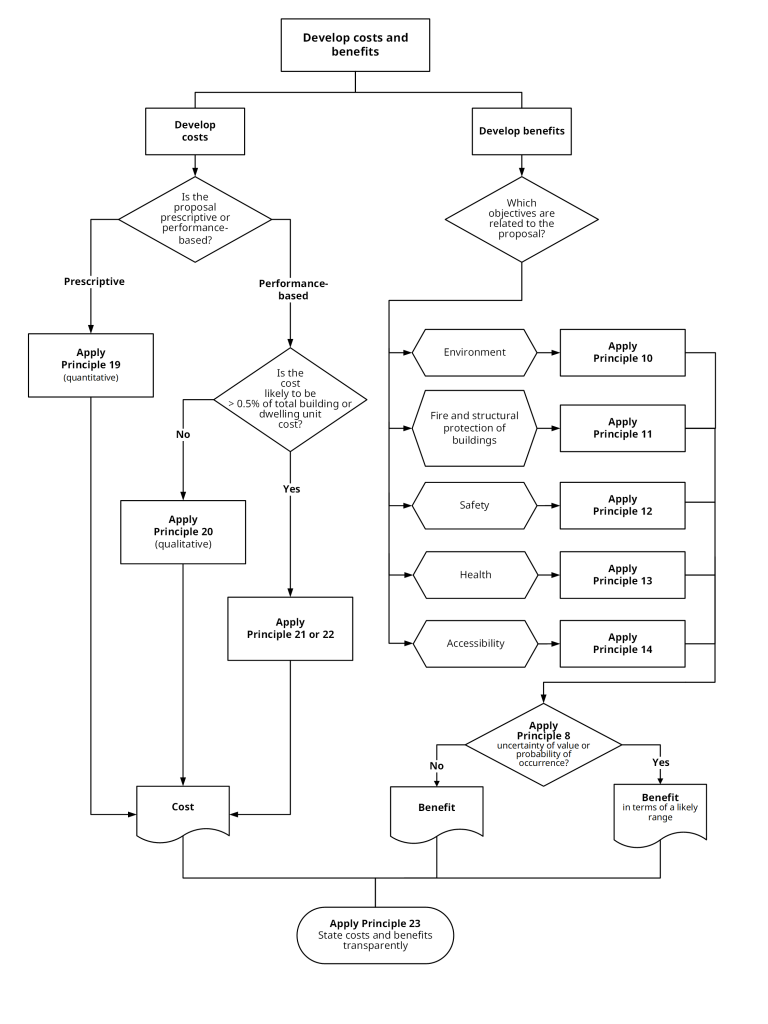

Figure 2 shows the impact analysis methods for proposed changes that are moderate or complex.

Figure 2: Developing the costs and benefits of a proposed change in a moderate or complex impact analysis

Text description of Figure 2

The chart provides a way to analyze a proposed change and asks yes, no, and other questions to evaluate the costs and benefits associated with the change. The chart has two main branches: Develop costs and Develop benefits.

Each branch has its own decision pathways.

Develop costs branch:

Question 1: Is the proposal prescriptive or performance-based?

- If your answer is Prescriptive, Principle 19, which specifies a quantitative cost analysis (or qualitative, under some circumstances), should be applied

- If your answer is Performance-based, go to question 2

Question 2: Is the cost likely to exceed 0.5% of the total building or dwelling unit cost?

- If your answer is Yes, then Principle 21 or 22, both of which specify a quantitative cost analysis, should be applied

- If your answer is No, Principle 20, which specifies a qualitative cost analysis, should be applied

All boxes labelled Principle in the Develop costs branch lead to the Cost box, which leads to Principle 23, which requires that all costs and benefits are stated transparently.

Develop benefits branch:

Question 1: Which approved objectives are related to the proposal?

- If your answer is Environment, apply Principle 10, which specifies the expression of benefits in quantitative terms, then go to question 2

- If your answer is Fire and structural protection of buildings, apply Principle 11, which specifies the expression of benefits in quantitative terms, then go to question 2

- If your answer is Safety, apply Principle 12, which specifies the expression of benefits in quantitative terms, then go to question 2

- If your answer is Health, apply Principle 13, which specifies the expression of benefits in quantitative terms, then go to question 2

- If your answer is Accessibility, apply Principle 14, which specifies the expression of benefits in quantitative terms, then go to question 2

Question 2: Apply Principle 8, which specifies what to do when there is uncertainty about the quantitative analysis of benefits

- If there is no uncertainty, go to Benefit

- If there is uncertainty, go to Benefit in terms of a likely range

Both the Benefit and Benefit in terms of a likely range boxes lead to Principle 23, which requires that all costs and benefits are stated transparently.

[1] Available upon request by contacting the CBHCC Secretary via email.